"landscape grading Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with landscape grading Las Vegas. Best Landscaping Las Vegas Nevada. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Expert Landscaping Services in Las Vegas Nevada. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape grading Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape soil Las Vegas","Embark on a journey toward landscape soil Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape soil Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape mulch Las Vegas","Open the door to landscape mulch Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape mulch Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape rocks Las Vegas","Experience unparalleled value in landscape rocks Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape rocks Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Landscaping Nevada . Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape boulders Las Vegas","Open the door to landscape boulders Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape boulders Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape trees Las Vegas","Immerse yourself in landscape trees Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape trees Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape shrubs Las Vegas","Combine style and function in landscape shrubs Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape shrubs Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape flowers Las Vegas","Embark on a journey toward landscape flowers Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Best Las Vegas Landscaping USA. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape flowers Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape turf Las Vegas","Open the door to landscape turf Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape turf Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape lawn care Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with landscape lawn care Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape lawn care Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape pest control Las Vegas","Explore a new dimension of landscape pest control Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape pest control Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape fertilization Las Vegas","Achieve remarkable results with landscape fertilization Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape fertilization Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape trimming Las Vegas","Immerse yourself in landscape trimming Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste.

"landscape pruning Las Vegas","Embrace the possibilities with landscape pruning Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape pruning Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape clean up Las Vegas","Explore a new dimension of landscape clean up Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape clean up Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape debris removal Las Vegas","Unleash the full beauty of landscape debris removal Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape debris removal Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape design ideas Las Vegas","Combine style and function in landscape design ideas Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape design ideas Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape inspiration Las Vegas","Reinvent your exterior with landscape inspiration Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens.

"landscape gallery Las Vegas","Achieve remarkable results with landscape gallery Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape gallery Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape portfolio Las Vegas","Optimize your property through landscape portfolio Las Vegas. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens. Incorporating region-specific materials leads to seamless integration with the surrounding desert environment. Our proven expertise in landscape portfolio Las Vegas ensures that each project receives a tailored approach. Ultimately, careful planning and professional expertise guarantee outstanding outdoor transformations."

"landscape estimates Las Vegas","Reach new heights of design with landscape estimates Las Vegas. Many companies focus on resource-saving techniques, including drip irrigation and drought-resistant plants. Professionals in this region craft visually appealing, water-conscious environments well-suited to desert conditions. By blending native plants, rock formations, and efficient irrigation, you can establish a long-lasting outdoor retreat. Customers can enjoy sustainable, vibrant spaces that also reduce water usage and routine upkeep. Whether you prefer minimalistic rock gardens or lush greenery, skilled experts can tailor designs to your taste. Thoughtful lighting and smart controllers help create an appealing ambiance while maximizing efficiency. Simple additions, like seating areas or decorative pavers, can turn unused corners into welcoming havens.

|

Las Vegas

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Etymology: from Spanish las vegas 'the meadows' | |

| Nicknames: | |

| Coordinates: 36°10′2″N 115°8′55″W / 36.16722°N 115.14861°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| County | Clark |

| Founded | May 15, 1905 |

| Incorporated | March 16, 1911 |

| Government

|

|

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Shelley Berkley (D) |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Brian Knudsen (D) |

| • City council |

Members

|

| • City manager | Jorge Cervantes |

| Area | |

|

• City

|

141.91 sq mi (367.53 km2) |

| • Land | 141.85 sq mi (367.40 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.14 km2) |

| • Urban

|

540 sq mi (1,400 km2) |

| • Metro

|

1,580 sq mi (4,100 km2) |

| Elevation

|

2,001 ft (610 m) |

| Population

(2020)

|

|

|

• City

|

641,903 |

| • Rank | 75th in North America 24th in the United States[6] 1st in Nevada |

| • Density | 4,525.16/sq mi (1,747.17/km2) |

| • Urban

|

2,196,623 (US: 21st) |

| • Urban density | 5,046.3/sq mi (1,948.4/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,265,461 (US: 29th) |

| Demonym | Las Vegan |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | $160.728 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

89044, 89054, 891xx

|

| Area code(s) | 702 and 725 |

| FIPS code | 32-40000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 847388 |

| Website | lasvegasnevada |

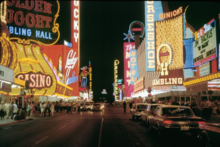

Las Vegas,[a] colloquially referred to as Vegas, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Nevada and the seat of Clark County. The Las Vegas Valley metropolitan area is the largest within the greater Mojave Desert, and second-largest in the Southwestern United States. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had 641,903 residents in 2020,[9] with a metropolitan population of 2,227,053,[10] making it the 24th-most populous city in the United States. Las Vegas is an internationally renowned major resort city, known primarily for its gambling, shopping, fine dining, entertainment, and nightlife, with most venues centered on downtown Las Vegas and more to the Las Vegas Strip just outside city limits in the unincorporated towns of Paradise and Winchester. The Las Vegas Valley serves as the leading financial, commercial, and cultural center in Nevada.

Las Vegas was settled in 1905 and officially incorporated in 1911.[11] At the close of the 20th century, it was the most populated North American city founded within that century (a similar distinction was earned by Chicago in the 19th century). Population growth has accelerated since the 1960s and into the 21st century, and between 1990 and 2000 the population increased by 85.2%.

The city bills itself as the Entertainment Capital of the World, and is famous for its luxurious and large casino-hotels. With over 40.8 million visitors annually as of 2023,[12] Las Vegas is one of the most visited cities in the United States, annually ranking as one of the world's most visited tourist destinations.[13][14] It is the third most popular U.S. destination for business conventions[15] and a global leader in the hospitality industry.[16] The city's tolerance for numerous forms of adult entertainment has earned it the nickname "Sin City",[17] and has made it a popular setting for literature, films, television programs, commercials and music videos.

In 1829, Mexican trader and explorer Antonio Armijo led a group consisting of 60 men and 100 mules along the Old Spanish Trail from modern day New Mexico to California. Along the way, the group stopped in what would become Las Vegas and noted its natural water sources, now referred to as the Las Vegas Springs, which supported extensive vegetation such as grasses and mesquite trees. The springs were a significant natural feature in the valley, with streams that supported a meadow ecosystem. This region served as the winter residence for the Southern Paiute people, who utilized the area's resources before moving to higher elevations during the summer months. The Spanish "las vegas" or "the meadows" (more precisely, lower land near a river) in English, was applied to describe the fertile lowlands near the springs. Over time, the name began to refer to the populated settlement.[18][19][20]

Nomadic Paleo-Indians traveled to the Las Vegas area 10,000 years ago, leaving behind petroglyphs. Ancient Puebloan and Paiute tribes followed at least 2,000 years ago.[21]

A young Mexican scout named Rafael Rivera is credited as the first non-Native American to encounter the valley, in 1829.[22] Trader Antonio Armijo led a 60-man party along the Spanish Trail to Los Angeles, California, in 1829.[23][24] In 1844, John C. Frémont arrived, and his writings helped lure pioneers to the area. Downtown Las Vegas's Fremont Street is named after him.

Eleven years later, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints chose Las Vegas as the site to build a fort halfway between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, where they would travel to gather supplies. The fort was abandoned several years afterward. The remainder of this Old Mormon Fort can still be seen at the intersection of Las Vegas Boulevard and Washington Avenue.

Las Vegas was founded as a city in 1905, when 110 acres (45 ha) of land adjacent to the Union Pacific Railroad tracks were auctioned in what would become the downtown area. In 1911, Las Vegas was incorporated as a city.[25]

The year 1931 was pivotal for Las Vegas. At that time, Nevada legalized casino gambling[26] and reduced residency requirements for divorce to six weeks.[27] This year also witnessed the beginning of construction of the tunnels of nearby Hoover Dam. The influx of construction workers and their families helped Las Vegas avoid economic calamity during the Great Depression. The construction work was completed in 1935.

In late 1941, Las Vegas Army Airfield was established. Renamed Nellis Air Force Base in 1950, it is now home to the United States Air Force Thunderbirds aerobatic team.[28]

Following World War II, lavishly decorated hotels, gambling casinos, and big-name entertainment became synonymous with Las Vegas.

In 1951, nuclear weapons testing began at the Nevada Test Site, 65 miles (105 km) northwest of Las Vegas. During this time, the city was nicknamed the "Atomic City." Residents and visitors were able to witness the mushroom clouds (and were exposed to the fallout) until 1963 when the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty required that nuclear tests be moved underground.[29]

In 1955, the Moulin Rouge Hotel opened and became the first racially integrated casino-hotel in Las Vegas.

During the 1960s, corporations and business tycoons such as Howard Hughes were building and buying hotel-casino properties. Gambling was referred to as "gaming," which transitioned it into a legitimate business. Learning from Las Vegas, published during this era, asked architects to take inspiration from the city's highly decorated buildings, helping to start the postmodern architecture movement.

In 1995, the Fremont Street Experience opened in Las Vegas's downtown area. This canopied five-block area features 12.5 million LED lights and 550,000 watts of sound from dusk until midnight during shows held at the top of each hour.

Due to the realization of many revitalization efforts, 2012 was dubbed "The Year of Downtown." Projects worth hundreds of millions of dollars made their debut at this time, including the Smith Center for the Performing Arts, the Discovery Children's Museum, the Mob Museum, the Neon Museum, a new City Hall complex, and renovations for a new Zappos.com corporate headquarters in the old City Hall building.[30][31]

Las Vegas is the county seat of Clark County, in a basin on the floor of the Mojave Desert,[32] and is surrounded by mountain ranges. Much of the landscape is rocky and arid, with desert vegetation and wildlife. It can be subjected to torrential flash floods, although much has been done to mitigate the effects of flash floods through improved drainage systems.[33]

The city's elevation is approximately 2,030 ft (620 m) above sea level, though the surrounding peaks reach elevations of over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and act as barriers to the strong flow of moisture from the surrounding area. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 135.86 sq mi (351.9 km2), of which 135.81 sq mi (351.7 km2) is land and 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) (0.03%) is water.

After Alaska and California, Nevada is the third most seismically active state in the U.S. It has been estimated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) that over the next 50 years, there is a 10–20% chance of an M6.0 or greater earthquake occurring within 50 km (31 mi) of Las Vegas.[34]

Within the city are many lawns, trees, and other greenery. Due to water resource issues, there has been a movement to encourage xeriscapes. Another part of conservation efforts is scheduled watering days for residential landscaping. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency grant in 2008 funded a program that analyzed and forecast growth and environmental effects through 2019.[35]

Las Vegas has a subtropical hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification: BWh, Trewartha climate classification BWhk), typical of the Mojave Desert in which it lies. This climate is typified by long, extremely hot summers; warm transitional seasons; and short winters with mild days and cool nights. There is abundant sunshine throughout the year, with an average of 310 sunny days and bright sunshine during 86% of all daylight hours.[36][37] Rainfall is scarce, with an average of 4.2 in (110 mm) dispersed between roughly 26 total rainy days per year.[38] Las Vegas is among the sunniest, driest, and least humid locations in North America, with exceptionally low dew points and humidity that sometimes remains below 10%.[39]

The summer months of June through September are extremely hot, though moderated by the low humidity levels. July is the hottest month, with an average daytime high of 104.5 °F (40.3 °C). On average, 137 days per year reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C), of which 78 days reach 100 °F (38 °C) and 10 days reach 110 °F (43 °C). During the peak intensity of summer, overnight lows frequently remain above 80 °F (27 °C), and occasionally above 85 °F (29 °C).[36]

While most summer days are consistently hot, dry, and cloudless, the North American Monsoon sporadically interrupts this pattern and brings more cloud cover, thunderstorms, lightning, increased humidity, and brief spells of heavy rain. Potential monsoons affect Las Vegas between July and August. Summer in Las Vegas is marked by significant diurnal temperature variation. While less extreme than other parts of the state, nighttime lows in Las Vegas are often 30 °F (16.7 °C) or more lower than daytime highs.[40] The average hottest night of the year is 90 °F (32 °C). The all-time record is at 95 °F (35 °C).[36]

Las Vegas winters are relatively short, with typically mild daytime temperatures and chilly nights. Sunshine is abundant in all seasons. December is both the year's coolest and cloudiest month, with an average daytime high of 56.9 °F (13.8 °C) and sunshine occurring during 78% of its daylight hours. Winter evenings are defined by clear skies and swift drops in temperature after sunset, with overnight minima averaging around 40 °F (4.4 °C) in December and January. Owing to its elevation that ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 feet (610 to 910 m), Las Vegas experiences markedly cooler winters than other areas of the Mojave Desert and the adjacent Sonoran Desert that are closer to sea level. The city records freezing temperatures an average of 10 nights per winter. It is exceptionally rare for temperatures to reach or fall below 25 °F (−4 °C).[36]

Most of the annual precipitation falls during the winter. February, the wettest month, averages only four days of measurable rain. The mountains immediately surrounding the Las Vegas Valley accumulate snow every winter, but significant accumulation within the city is rare, although moderate accumulations occur every few years. The most recent accumulations occurred on February 18, 2019, when parts of the city received about 1 to 2 inches (2.5 to 5.1 cm) of snow[41] and on February 20 when the city received almost 0.5 inches (1.3 cm).[42] Other recent significant snow accumulations occurred on December 25, 2015, and December 17, 2008.[43] Unofficially, Las Vegas's largest snowfall on record was the 12 inches (30 cm) that fell in 1909.[44] In recent times, ice days have not occurred, although 29 °F (−2 °C) was measured in 1963.[36] On average the coldest day is 44 °F (7 °C).[36]

The highest temperature officially observed for Las Vegas is 120 °F (48.9 °C), as measured at Harry Reid International Airport on July 7, 2024.[36][45] The lowest temperature was 8 °F (−13 °C), recorded on two days: January 25, 1937, and January 13, 1963.[36] The official record hot daily minimum is 95 °F (35 °C) on July 19, 2005, and July 1, 2013. The official record cold daily maximum is 28 °F (−2 °C) on January 8 and 21, 1937.[36] July 2024 was the hottest month ever recorded in Las Vegas, with its highest recorded mean daily average temperature over the month of 99.9 °F (38 °C), its highest recorded mean daily maximum temperature of 111.5 °F (44 °C), and its highest recorded mean nightly minimum temperature of 88.3 °F (31 °C).[46]

Due to concerns about climate change in the wake of a 2002 drought, daily water consumption has been reduced from 314 US gallons (1,190 L) per resident in 2003 to around 205 US gallons (780 L) in 2015.[47]

| Climate data for Harry Reid International Airport (Paradise, Nevada), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1937–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

87 (31) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

109 (43) |

117 (47) |

120 (49) |

116 (47) |

114 (46) |

104 (40) |

87 (31) |

78 (26) |

120 (49) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.7 (20.4) |

74.2 (23.4) |

84.3 (29.1) |

93.6 (34.2) |

101.8 (38.8) |

110.1 (43.4) |

112.9 (44.9) |

110.3 (43.5) |

105.0 (40.6) |

94.6 (34.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

67.9 (19.9) |

113.6 (45.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.5 (14.7) |

62.9 (17.2) |

71.1 (21.7) |

78.5 (25.8) |

88.5 (31.4) |

99.4 (37.4) |

104.5 (40.3) |

102.8 (39.3) |

94.9 (34.9) |

81.2 (27.3) |

67.1 (19.5) |

56.9 (13.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 49.5 (9.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

67.7 (19.8) |

77.3 (25.2) |

87.6 (30.9) |

93.2 (34.0) |

91.7 (33.2) |

83.6 (28.7) |

70.4 (21.3) |

57.2 (14.0) |

48.2 (9.0) |

70.1 (21.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.5 (4.7) |

44.1 (6.7) |

50.5 (10.3) |

56.9 (13.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

75.8 (24.3) |

82.0 (27.8) |

80.6 (27.0) |

72.4 (22.4) |

59.6 (15.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

39.6 (4.2) |

59.6 (15.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

32.9 (0.5) |

38.7 (3.7) |

45.2 (7.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

60.8 (16.0) |

47.4 (8.6) |

35.2 (1.8) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) |

16 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

31 (−1) |

38 (3) |

48 (9) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

43 (6) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

11 (−12) |

8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.56 (14) |

0.80 (20) |

0.42 (11) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.45 (11) |

4.18 (106) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 25.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 45.1 | 39.6 | 33.1 | 25.0 | 21.3 | 16.5 | 21.1 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 28.8 | 37.2 | 45.0 | 30.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 22.1 (−5.5) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

40.6 (4.8) |

44.1 (6.7) |

37.0 (2.8) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

29.4 (−1.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 245.2 | 246.7 | 314.6 | 346.1 | 388.1 | 401.7 | 390.9 | 368.5 | 337.1 | 304.4 | 246.0 | 236.0 | 3,825.3 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 79 | 81 | 85 | 88 | 89 | 92 | 88 | 88 | 91 | 87 | 80 | 78 | 86 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[36][38][37] | |||||||||||||

|

|

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org.

|

See or edit raw graph data.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 25 | — | |

| 1910 | 800 | 3,100.0% | |

| 1920 | 2,304 | 188.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,165 | 124.2% | |

| 1940 | 8,422 | 63.1% | |

| 1950 | 24,624 | 192.4% | |

| 1960 | 64,405 | 161.6% | |

| 1970 | 125,787 | 95.3% | |

| 1980 | 164,674 | 30.9% | |

| 1990 | 258,295 | 56.9% | |

| 2000 | 478,434 | 85.2% | |

| 2010 | 583,756 | 22.0% | |

| 2020 | 641,903 | 10.0% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 656,274 | 2.2% | |

| source:[48][49] 2010–2010[9] |

|||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[50] | Pop 2010[51] | Pop 2020[52] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 277,704 | 279,703 | 259,561 | 58.04% | 47.91% | 40.44% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 48,380 | 62,008 | 79,129 | 10.11% | 10.62% | 12.33% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 2,405 | 2,391 | 2,291 | 0.50% | 0.41% | 0.36% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 22,411 | 34,606 | 44,995 | 4.68% | 5.93% | 7.01% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 1,935 | 3,103 | 4,204 | 0.40% | 0.53% | 0.65% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 650 | 1,101 | 3,855 | 0.14% | 0.19% | 0.60% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 11,987 | 16,985 | 34,040 | 2.51% | 2.91% | 5.30% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 112,962 | 183,859 | 213,828 | 23.61% | 31.50% | 33.31% |

| Total | 474,434 | 583,756 | 641,903 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

According to the 2020 United States census, the city of Las Vegas had 644,883 people living in 244,429 households. The racial composition of the City of Las Vegas was 49.2% white, 11.9% black, 1.1% American Indian or Alaska Native, 6.9% Asian, Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 34.1% and 16.2% from two or more races. 40.8% were non-Hispanic white.[53]

Approximately 5.8% of residents are under the age of five, 22.8% under the age of eighteen and 15.6% over 65 years old. Females are 50.0% of the total population.[53]

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Other

From 2019 to 2023, Las Vegas had approximately 244,429 households, with an average of 2.63 persons per household. About 55.7% of housing units were owner-occupied, and the median value of owner-occupied housing was $395,300. Median gross rent during this period was $1,456 per month (in 2023 dollars).[53]

The median household income in Las Vegas from 2019 to 2023 was $70,723, while the per capita income was $38,421 (in 2023 dollars). Approximately 14.2% of the population lived below the poverty line during the same period.[53]

Residents over 25 years old with a high school diploma were 85.8% of the population with 27.3% having attained a bachelor's degree or higher.[53]

About 33.0% of residents aged 5 and older speak a language other than English at home. 20.9% of residents are foreign-born.[53]

The mean travel time to work for residents aged 16 and older was approximately 25.8 minutes between 2019 and 2023. The vast majority of households in Las Vegas are digitally connected, with 95.6% having a computer and 89.1% subscribing to broadband internet services .

According to demographer William H. Frey using data from the 2010 United States census, Las Vegas has the second-lowest level of black-white segregation of any of the 100 largest U.S. metropolitan areas after Tucson, Arizona.[54]

According to the Las Vegas Asian Chamber of Commerce, Filipinos make up the largest ethnic population within Vegas. at 20% of the city's population.[55] Native Hawaiians are also a major demographic in the city, with some Hawaiians and Las Vegas residents calling the city the "ninth island of Hawaii" due to the major influx of Hawaiians to Vegas.[56]

According to a 2004 study, Las Vegas has one of the highest divorce rates.[57][58] The city's high divorce rate is not wholly due to Las Vegans themselves getting divorced. Compared to other states, Nevada's nonrestrictive requirements for divorce result in many couples temporarily moving to Las Vegas in order to get divorced.[59] Similarly, Nevada marriage requirements are equally lax resulting in one of the highest marriage rates of U.S. cities, with many licenses issued to people from outside the area (see Las Vegas weddings).[59]

According to the 2010 Census, the city of Las Vegas had a population of 583,756. The city's racial composition had shifted slightly, with 47.91% of the population identifying as White alone (non-Hispanic), 10.63% as Black or African American alone (non-Hispanic), 0.41% as Native American or Alaska Native alone (non-Hispanic), 5.93% as Asian alone (non-Hispanic), 0.53% as Pacific Islander alone (non-Hispanic), 0.19% as Other Race alone (non-Hispanic), and 2.91% as Mixed race or Multiracial (non-Hispanic). Hispanic or Latino individuals of any race represented 31.50% of the population.[51]

According to the 2000 census, Las Vegas had a population of 474,434 people. The racial makeup of the city was 58.52% White alone (non-Hispanic), 10.19% Black or African American alone (non-Hispanic), 0.51% Native American or Alaska Native alone (non-Hispanic), 4.72% Asian alone (non-Hispanic), 0.41% Pacific Islander alone (non-Hispanic), 0.14% Other Race alone (non-Hispanic), and 2.52% Mixed race or Multiracial (non-Hispanic). Hispanic or Latino individuals of any race made up 23.81% of the population.[50]

| Historical racial profile | 2020[60] | 2010[61] | 2000[62] | 1990[63] | 1970[63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 46.0% | 62.1% | 69.9% | 78.4% | 87.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic Whites | 40.4% | 47.9% | 58.0% | 72.1% | 83.1%[c] |

| Black or African American | 12.9% | 11.1% | 10.4% | 11.4% | 11.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 33.3% | 31.5% | 23.6% | 12.5% | 4.6%[c] |

| Asian | 7.2% | 6.1% | 4.8% | 3.6% | 0.7% |

The primary drivers of the Las Vegas economy are tourism, gaming, and conventions, which in turn feed the retail and restaurant industries.

The major attractions in Las Vegas are the casinos and the hotels, although in recent years other new attractions have begun to emerge.

Most casinos in the downtown area are on Fremont Street, with The STRAT Hotel, Casino & Skypod as one of the few exceptions. Fremont East, adjacent to the Fremont Street Experience, was granted variances to allow bars to be closer together, similar to the Gaslamp Quarter of San Diego, the goal being to attract a different demographic than the Strip attracts.

The Golden Gate Hotel and Casino, downtown along the Fremont Street Experience, is the oldest continuously operating hotel and casino in Las Vegas; it opened in 1906 as the Hotel Nevada.

In 1931, the Northern Club (now the La Bayou) opened.[64][65] The most notable of the early casinos may have been Binion's Horseshoe (now Binion's Gambling Hall and Hotel) while it was run by Benny Binion.

Boyd Gaming has a major presence downtown operating the California Hotel & Casino, the Fremont Hotel & Casino, and the Main Street Casino. The Four Queens also operates downtown along the Fremont Street Experience.

Downtown casinos that have undergone major renovations and revitalization in recent years include the Golden Nugget Las Vegas, The D Las Vegas (formerly Fitzgerald's), the Downtown Grand Las Vegas (formerly Lady Luck), the El Cortez Hotel & Casino, and the Plaza Hotel & Casino.[66]

In 2020, Circa Resort & Casino opened, becoming the first all-new hotel-casino to be built on Fremont Street since 1980.[67]

The center of the gambling and entertainment industry is the Las Vegas Strip, outside the city limits in the surrounding unincorporated communities of Paradise and Winchester in Clark County. Some of the largest casinos and buildings are there.[68]

In 1929, the city installed a welcome arch over Fremont Street, at the corner of Main Street.[69][70][71] It remained in place until 1931.[72][73]

In 1959, the 25-foot-tall (7.6 m) Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign was installed at the south end of the Las Vegas Strip. A replica welcome sign, standing nearly 16 feet (4.9 m) tall, was installed within city limits in 2002, at Las Vegas Boulevard and Fourth Street.[74][75][76] The replica was destroyed in 2016, when a pickup truck crashed into it.[77]

In 2018, the city approved plans for a new gateway landmark in the form of neon arches. It was built within city limits, in front of the Strat resort and north of Sahara Avenue.[78] The project, built by YESCO, cost $6.5 million and stands 80 feet (24 m) high.[79] Officially known as the Gateway Arches, the project was completed in 2020. The steel arches are blue during the day, and light up in a variety of colors at night.[80]

Also located just north of the Strat are a pair of giant neon showgirls, initially added in 2018 as part of a $400,000 welcome display. The original showgirls were 25 feet (7.6 m) tall, but were replaced by new ones in 2022, rising 50 feet (15 m).[81][82] The originals were refurbished following weather damage and installed at the Las Vegas Arts District.[82][83]

When The Mirage opened in 1989, it started a trend of major resort development on the Las Vegas Strip outside of the city. This resulted in a drop in tourism in the downtown area, but many recent projects have increased the number of visitors to downtown.

An effort has been made by city officials to diversify the economy by attracting health-related, high-tech and other commercial interests. No state tax for individuals or corporations, as well as a lack of other forms of business-related taxes, have aided the success of these efforts.[84]

The Fremont Street Experience was built in an effort to draw tourists back to the area and has been popular since its startup in 1995.

The city conducted a land-swap deal in 2000 with Lehman Brothers, acquiring 61 acres (25 ha) of property near downtown Las Vegas in exchange for 91 acres (37 ha) of the Las Vegas Technology Center.[85] In 2004, Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman announced that the area would become home to Symphony Park (originally called "Union Park"[86]), a mixed-use development. The development is home to the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, The Smith Center for the Performing Arts, the Discovery Children's Museum, the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, and four residential projects totaling 600 residential units as of 2024.[87]

In 2005, the World Market Center opened, consisting of three large buildings taking up 5,400,000 square feet (500,000 m2). Trade shows for the furniture and furnishing industries are held there semiannually.[88]

Also nearby is the Las Vegas North Premium Outlets. With a second expansion, completed in May 2015, the mall currently offers 175 stores.[89]

City offices moved to a new Las Vegas City Hall in February 2013 on downtown's Main Street. The former city hall building is now occupied by the corporate headquarters for the online retailer Zappos.com, which opened downtown in 2013. Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh took an interest in the urban area and contributed $350 million toward a revitalization effort called the Downtown Project.[90][91] Projects funded include Las Vegas's first independent bookstore, The Writer's Block.[92]

A number of new industries have moved to Las Vegas in recent decades. Zappos.com (now an Amazon subsidiary) was founded in San Francisco but by 2013 had moved its headquarters to downtown Las Vegas. Allegiant Air, a low-cost air carrier, launched in 1997 with its first hub at Harry Reid International Airport and headquarters in nearby Summerlin.

Planet 13 Holdings, a cannabis company, opened the world's largest cannabis dispensary in Las Vegas at 112,000 sq ft (10,400 m2).[93][94]

A growing population means the Las Vegas Valley used 1.2 billion US gal (4.5 billion L) more water in 2014 than in 2011. Although water conservation efforts implemented in the wake of a 2002 drought have had some success, local water consumption remains 30 percent greater than in Los Angeles, and over three times that of San Francisco metropolitan area residents. The Southern Nevada Water Authority is building a $1.4 billion tunnel and pumping station to bring water from Lake Mead, has purchased water rights throughout Nevada, and has planned a controversial $3.2 billion pipeline across half the state. By law, the Las Vegas Water Service District "may deny any request for a water commitment or request for a water connection if the District has an inadequate supply of water." But limiting growth on the basis of an inadequate water supply has been unpopular with the casino and building industries.[47]

The city is home to several museums, including the Neon Museum (the location for many of the historical signs from Las Vegas's mid-20th century heyday), The Mob Museum, the Las Vegas Natural History Museum, the Discovery Children's Museum, the Nevada State Museum and the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park.

The city is home to an extensive Downtown Arts District, which hosts numerous galleries and events including the annual Las Vegas Film Festival. "First Friday" is a monthly celebration that includes arts, music, special presentations and food in a section of the city's downtown region called 18b, The Las Vegas Arts District.[95] The festival extends into the Fremont East Entertainment District.[96] The Thursday evening before First Friday is known in the arts district as "Preview Thursday," which highlights new gallery exhibitions throughout the district.[97]

The Las Vegas Academy of International Studies, Performing and Visual Arts is a Grammy award-winning magnet school located in downtown Las Vegas. The Smith Center for the Performing Arts is downtown in Symphony Park and hosts various Broadway shows and other artistic performances.

Las Vegas has earned the moniker "Gambling Capital of the World," as it has the world's most land-based casinos.[98] The city is also host to more AAA Five Diamond hotels than any other city in the world.[99]

The Las Vegas Valley is the home of three major professional teams: the National Hockey League (NHL)'s Vegas Golden Knights, an expansion team that began play in the 2017–18 NHL season at T-Mobile Arena in nearby Paradise,[100] the National Football League (NFL)'s Las Vegas Raiders, who relocated from Oakland, California, in 2020 and play at Allegiant Stadium in Paradise,[101] and the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA)'s Las Vegas Aces, who play at the Mandalay Bay Events Center. The Oakland Athletics of Major League Baseball (MLB) will move to Las Vegas by 2028.[102][103]

Two minor league sports teams play in the Las Vegas area. The Las Vegas Aviators of the Pacific Coast League, the Triple-A farm club of the Athletics, play at Las Vegas Ballpark in nearby Summerlin.[104] The Las Vegas Lights FC of the United Soccer League play in Cashman Field in Downtown Las Vegas.[105][106]

The mixed martial arts promotion, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), is headquartered in Las Vegas and also frequently holds fights in the city at T-Mobile Arena and at the UFC Apex training facility near the headquarters.[107]

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Vegas Raiders | Football | NFL | Allegiant Stadium (65,000) | 2020 | 3[d] |

| Vegas Golden Knights | Ice hockey | NHL | T-Mobile Arena (17,500) | 2017 | 1 |

| Las Vegas Aces | Women's basketball | WNBA | Michelob Ultra Arena (12,000) | 2018 | 2 |

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Vegas Aviators | Baseball | MiLB (AAA-PCL) | Las Vegas Ballpark (10,000) | 1983 | 2 |

| Henderson Silver Knights | Ice hockey | AHL | Lee's Family Forum (5,567) | 2020 | 0 |

| Las Vegas Lights FC | Soccer | USLC | Cashman Field (9,334) | 2018 | 0 |

| Vegas Knight Hawks | Indoor football | IFL | Lee's Family Forum (6,019) | 2021 | 0 |

| Las Vegas Desert Dogs | Box lacrosse | NLL | Lee's Family Forum (5,567) | 0 |

| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Vegas Dream | Basketball | ABA | 2023 | ||

| Las Vegas Royals | 2020 | ||||

| Vegas Jesters | Ice hockey | MWHL | City National Arena (600) | 2012 | 0 |

| Las Vegas Thunderbirds | USPHL | 2019 | 0 | ||

| Las Vegas Legends | Soccer | NPSL | Peter Johann Memorial Field (2,500) | 2021 | 0 |

| Vegas NVaders | Women's football | WFA - D2 | Desert Pines High School (N/A) | 2023 | 0 |

| School | Team | League | Division | Primary Conference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) | UNLV Rebels | NCAA | NCAA Division I | Mountain West |

| College of Southern Nevada (CSN) | CSN Coyotes | NJCAA | NJCAA Division I | Scenic West |

The city's parks and recreation department operates 78 regional, community, neighborhood, and pocket parks; four municipal swimming poools, 11 recreational centers, four active adult centers, eight cultural centers, six galleries, eleven dog parks, and four golf courses: Angel Park Golf Club, Desert Pines Golf Club, Durango Hills Golf Club, and the Las Vegas Municipal Golf Course.[108]

It is also responsible for 123 playgrounds, 23 softball fields, 10 football fields, 44 soccer fields, 10 dog parks, six community centers, four senior centers, 109 skate parks, and six swimming pools.[109]

The city of Las Vegas has a council–manager government.[110] The mayor sits as a council member-at-large and presides over all city council meetings.[110] If the mayor cannot preside over a city council meeting, then the Mayor pro tempore is the presiding officer of the meeting until the Mayor returns to his/her seat.[111] The city manager is responsible for the administration and the day-to-day operations of all municipal services and city departments.[112] The city manager maintains intergovernmental relationships with federal, state, county and other local governments.[112]

Out of the 2,265,461 people in Clark County as of the 2020 Census, approximately 1,030,000 people live in unincorporated Clark County, and around 650,000 live in incorporated cities such as North Las Vegas, Henderson and Boulder City.[113] Las Vegas and Clark County share a police department, the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, which was formed after a 1973 merger of the Las Vegas Police Department and the Clark County Sheriff's Department.[114] North Las Vegas, Henderson, Boulder City, Mesquite, UNLV and CCSD have their own police departments.[115]

The federally-recognized Las Vegas Tribe of Paiute Indians (Southern Paiute: Nuvagantucimi) occupies a 31-acre (130,000 m2) reservation just north downtown between Interstate-15 and Main Street.[116][117][118]

Downtown is the location of Lloyd D. George Federal District Courthouse[119] and the Regional Justice Center,[120] draws numerous companies providing bail, marriage, divorce, tax, incorporation and other legal services.

| Name | Position | Party | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shelley Berkley | Mayor | Democratic | [121] | |

| Brian Knudsen | 1st Ward Council member | Democratic | [122][123] | Mayor Pro Tem |

| Victoria Seaman | 2nd Ward Council member | Republican | [124][123] | |

| Olivia Diaz | 3rd Ward Council member | Democratic | [125][123] | |

| Francis Allen-Palenske | 4th Ward Council member | Republican | ||

| Shondra Summers-Armstrong | 5th Ward Council member | Democratic | [126] | |

| Nancy Brune | 6th Ward Council member | Democratic |

Primary and secondary public education is provided by the Clark County School District.[127]

Public higher education is provided by the Nevada System of Higher Education (NSHE). Public institutions serving Las Vegas include the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), the College of Southern Nevada (CSN), Nevada State University (NSU), and the Desert Research Institute (DRI).[128]

UNLV is a public, land-grant, R1 research university and is home to the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine[129] and the William S. Boyd School of Law, the only law school in Nevada.[130] The university's campus is urban and located about two miles east of the Las Vegas strip. The Desert Research Institute's southern campus sits next to UNLV, while its northern campus is in Reno.[131]

CSN, with campuses throughout Clark County,[132] is a community college with one of the largest enrollments in the United States.[133] In unincorporated Clark County, CSN's Charleston campus is home to the headquarters of Nevada Public Radio (KNPR), an NPR member station.[134][135]

Touro University Nevada located in Henderson is a non-profit, private institution primarily focusing on medical education.[136] Other institutions include a number of for-profit private schools (e.g., Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts, DeVry University, among others).[137]

Las Vegas is served by 10 full power television stations and 46 radio stations. The area is also served by two NOAA Weather Radio transmitters (162.55 MHz located in Boulder City and 162.40 MHz located on Potosi Mountain).

RTC Transit is a public transportation system providing bus service throughout Las Vegas, Henderson, North Las Vegas and other areas of the valley. Inter-city bus service to and from Las Vegas is provided by Greyhound, BoltBus, Orange Belt Stages, Tufesa, and several smaller carriers.[144]

Amtrak trains have not served Las Vegas since the service via the Desert Wind at Las Vegas station ceased in 1997, but Amtrak California operates Amtrak Thruway dedicated service between the city and its passenger rail stations in Bakersfield, California, as well as Los Angeles Union Station via Barstow.[145]

High-speed rail project Brightline West began construction in 2024 to connect Brightline's Las Vegas station and the Rancho Cucamonga station in Greater Los Angeles.[146]

The Las Vegas Monorail on the Strip was privately built, and upon bankruptcy taken over by the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.[147]

Silver Rider Transit operates three routes within Las Vegas, offering connections to Laughlin,[148] Mesquite,[149] and Sandy Valley.[150]

The Union Pacific Railroad is the only Class I railroad providing rail freight service to the city. Until 1997, the Amtrak Desert Wind train service ran through Las Vegas using the Union Pacific Railroad tracks.

In March 2010, the RTC launched bus rapid transit link in Las Vegas called the Strip & Downtown Express with limited stops and frequent service that connects downtown Las Vegas, the Strip and the Las Vegas Convention Center. Shortly after the launch, the RTC dropped the ACE name.[151]

In 2016, 77.1 percent of working Las Vegas residents (those living in the city, but not necessarily working in the city) commuted by driving alone. About 11 percent commuted via carpool, 3.9 percent used public transportation, and 1.4 percent walked. About 2.3 percent of Las Vegas commuters used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 4.3% of working Las Vegas residents worked at home.[152] In 2015, 10.2 percent of city of Las Vegas households were without a car, which increased slightly to 10.5 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Las Vegas averaged 1.63 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.

With some exceptions, including Las Vegas Boulevard, Boulder Highway (SR 582) and Rancho Drive (SR 599), the majority of surface streets in Las Vegas are laid out in a grid along Public Land Survey System section lines. Many are maintained by the Nevada Department of Transportation as state highways. The street numbering system is divided by the following streets:

Interstates 15, 11, and US 95 lead out of the city in four directions. Two major freeways – Interstate 15 and Interstate 11/U.S. Route 95 – cross in downtown Las Vegas. I-15 connects Las Vegas to Los Angeles, and heads northeast to and beyond Salt Lake City. I-11 goes northwest to the Las Vegas Paiute Indian Reservation and southeast to Henderson and to the Mike O'Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge, where from this point I-11 will eventually continue along US 93 towards Phoenix, Arizona. US 95 (and eventually I-11) connects the city to northwestern Nevada, including Carson City and Reno. US 93 splits from I-15 northeast of Las Vegas and goes north through the eastern part of the state, serving Ely and Wells. US 95 heads south from US 93 near Henderson through far eastern California. A partial beltway has been built, consisting of Interstate 215 on the south and Clark County 215 on the west and north. Other radial routes include Blue Diamond Road (SR 160) to Pahrump and Lake Mead Boulevard (SR 147) to Lake Mead.

East–west roads, north to south[153]

Harry Reid International Airport handles international and domestic flights into the Las Vegas Valley. The airport also serves private aircraft and freight/cargo flights. Most general aviation traffic uses the smaller North Las Vegas Airport and Henderson Executive Airport.

Exposures 50 years ago still have health implications today that will continue into the future...Deposition...generally decreases with distance from the test site in the direction of the prevailing wind across North America, although isolated locations received significant deposition as a result of rainfall. Trajectories of the fallout debris clouds across the U.S. are shown for four altitudes. Each dot indicates six hours.

"Probability of an earthquake of magnitude 6.0 or greater occurring within 50 km in 50 years (from USGS probabilistic seismic hazard analysis) 10–20% chance for Las Vegas area, magnitude 6".

|

|

This article possibly contains original research. (July 2016)

|

A lawn (/lÉâ€ÂÂÂËÂÂÂÂn/) is an area of soil-covered land planted with grasses and other durable plants such as clover which are maintained at a short height with a lawn mower (or sometimes grazing animals) and used for aesthetic and recreational purposes—it is also commonly referred to as part of a garden. Lawns are usually composed only of grass species, subject to weed and pest control, maintained in a green color (e.g., by watering), and are regularly mowed to ensure an acceptable length.[1] Lawns are used around houses, apartments, commercial buildings and offices. Many city parks also have large lawn areas. In recreational contexts, the specialised names turf, parade, pitch, field or green may be used, depending on the sport and the continent.

The term "lawn", referring to a managed grass space, dates to at least the 16th century. With suburban expansion, the lawn has become culturally ingrained in some areas of the world as part of the desired household aesthetic.[2] However, awareness of the negative environmental impact of this ideal is growing.[3] In some jurisdictions where there are water shortages, local government authorities are encouraging alternatives to lawns to reduce water use. Researchers in the United States have noted that suburban lawns are "biological deserts" that are contributing to a "continental-scale ecological homogenization."[4] Lawn maintenance practices also cause biodiversity loss in surrounding areas.[5][6] Some forms of lawn, such as tapestry lawns, are designed partly for biodiversity and pollinator support.

Lawn is a cognate of Welsh llan ( Cornish and Breton *lann* which is derived from the Common Brittonic word landa (Old French: lande) that originally meant heath, barren land, or clearing.[7][8]

Areas of grass grazed regularly by rabbits, horses or sheep over a long period often form a very low, tight sward similar to a modern lawn. This was the original meaning of the word "lawn", and the term can still be found in place names. Some forest areas where extensive grazing is practiced still have these seminatural lawns. For example, in the New Forest, England, such grazed areas are common, and are known as lawns, for example Balmer Lawn.[citation needed]

Lawns may have originated as grassed enclosures within early medieval settlements used for communal grazing of livestock, as distinct from fields reserved for agriculture.[citation needed] Low, mown-meadow areas may also have been valued because they allowed those inside an enclosed fence or castle to view those approaching. The early lawns were not always distinguishable from pasture fields. The damp climate of maritime Western Europe in the north made lawns possible to grow and manage. They were not a part of gardens in most other regions and cultures of the world until contemporary influence.[9]

In 1100s Britain, low-growing area of grasses and meadow flowers were grazed or scythed to keep them short, and used for sport.[10] Lawn bowling, which began in the 12th or 13th century, required short turf.[10]

Establishing grass using sod instead of seed was first documented in a Japanese text of 1159.[10]

Lawns became popular with the aristocracy in northern Europe from the Middle Ages onward. In the fourteen hundreds, open expanses of low grasses appear in paintings of public and private areas; by the fifteen hundreds, such areas were found in the gardens of the wealthy across northern and central Europe. Public meadow areas, kept short by sheep, were used for new sports such as cricket, soccer, and golf.[10] The word "laune" is first attested in 1540 from the Old French lande "heath, moor, barren land; clearing".[11] It initially described a natural opening in a woodland.[10] In the sixteen hundreds, "lawn" came to mean a grassy stretch of untilled land, and by mid-century, there were publications on seeding and transplanting sod. In the seventeen hundreds, "lawn" came to mean specifically a mown stretch of meadow.[10]

Lawns similar to those of today first appeared in France and England in the 1700s when André Le Nôtre designed the gardens of the Palace of Versailles that included a small area of grass called the tapis vert, or "green carpet", which became a common feature of French gardens. Large, mown open spaces became popular in Europe and North America.[10] The lawn was influenced by later seventeen-hundreds trends replicating the romantic aestheticism of grassy pastoralism from Italian landscape paintings.[12]

Before the invention of mowing machines in 1830, lawns were managed very differently. They were an element of wealthy estates and manor houses, and in some places were maintained by labor-intensive scything and shearing (for hay or silage). They were also pasture land maintained through grazing by sheep or other livestock.[citation needed]

It was not until the 17th and 18th century that the garden and the lawn became a place created first as walkways and social areas. They were made up of meadow plants, such as camomile, a particular favourite (see camomile lawn). In the early 17th century, the Jacobean epoch of gardening began; during this period, the closely cut "English" lawn was born. By the end of this period, the English lawn was a symbol of status of the aristocracy and gentry.[citation needed]

In the early 18th century, landscape gardening for the aristocracy entered a golden age, under the direction of William Kent and Lancelot "Capability" Brown. They refined the English landscape garden style with the design of natural, or "romantic", estate settings for wealthy Englishmen.[13] Brown, remembered as "England's greatest gardener", designed over 170 parks, many of which still endure. His influence was so great that the contributions to the English garden made by his predecessors Charles Bridgeman and William Kent are often overlooked.[14]

His work still endures at Croome Court (where he also designed the house), Blenheim Palace, Warwick Castle, Harewood House, Bowood House, Milton Abbey (and nearby Milton Abbas village), in traces at Kew Gardens and many other locations.[15] His style of smooth undulating lawns which ran seamlessly to the house and meadow, clumps, belts and scattering of trees and his serpentine lakes formed by invisibly damming small rivers, were a new style within the English landscape, a "gardenless" form of landscape gardening, which swept away almost all the remnants of previous formally patterned styles. His landscapes were fundamentally different from what they replaced, the well-known formal gardens of England which were criticised by Alexander Pope and others from the 1710s.[16]

The open "English style" of parkland first spread across Britain and Ireland, and then across Europe, such as the garden à la française being replaced by the French landscape garden. By this time, the word "lawn" in England had semantically shifted to describe a piece of a garden covered with grass and closely mown.[17]

Wealthy families in America during the late 18th century also began mimicking English landscaping styles. British settlers in North America imported an affinity for landscapes in the style of the English lawn. However, early in the colonization of the continent, environments with thick, low-growing, grass-dominated vegetation were rare in the eastern part of the continent, enough so that settlers were warned that it would be difficult to find land suitable for grazing cattle.[18] In 1780, the Shaker community began the first industrial production of high-quality grass seed in North America, and a number of seed companies and nurseries were founded in Philadelphia. The increased availability of these grasses meant they were in plentiful supply for parks and residential areas, not just livestock.[17]

Thomas Jefferson has long been given credit for being the first person to attempt an English-style lawn at his estate, Monticello, in 1806, but many others had tried to emulate English landscaping before he did. Over time, an increasing number towns in New England began to emphasize grass spaces. Many scholars link this development to the romantic and transcendentalist movements of the 19th century. These green commons were also heavily associated with the success of the Revolutionary War and often became the homes of patriotic war memorials after the Civil War ended in 1865.[17]

Before the mechanical lawn mower, the upkeep of lawns was possible only for the extremely wealthy estates and manor houses of the aristocracy. Labor-intensive methods of scything and shearing the grass were required to maintain the lawn in its correct state, and most of the land in England was required for more functional, agricultural purposes.[citation needed]

This all changed with the invention of the lawn mower by Edwin Beard Budding in 1830. Budding had the idea for a lawn mower after seeing a machine in a local cloth mill which used a cutting cylinder (or bladed reel) mounted on a bench to trim the irregular nap from the surface of woolen cloth and give a smooth finish.[19] Budding realised that a similar device could be used to cut grass if the mechanism was mounted in a wheeled frame to make the blades rotate close to the lawn's surface. His mower design was to be used primarily to cut the lawn on sports grounds and extensive gardens, as a superior alternative to the scythe, and he was granted a British patent on 31 August 1830.[20]

Budding went into partnership with a local engineer, John Ferrabee, who paid the costs of development and acquired rights to manufacture and sell lawn mowers and to license other manufacturers. Together they made mowers in a factory at Thrupp near Stroud.[21] Among the other companies manufacturing under license the most successful was Ransomes, Sims & Jefferies of Ipswich which began mower production as early as 1832.[22]

However, his model had two crucial drawbacks. It was immensely heavy (it was made of cast iron) and difficult to manoeuvre in the garden, and did not cut the grass very well. The blade would often spin above the grass uselessly.[22] It took ten more years and further innovations, including the advent of the Bessemer process for the production of the much lighter alloy steel and advances in motorization such as the drive chain, for the lawn mower to become a practical proposition. Middle-class families across the country, in imitation of aristocratic landscape gardens, began to grow finely trimmed lawns in their back gardens.[citation needed]

In the 1850s, Thomas Green of Leeds introduced a revolutionary mower design called the Silens Messor (meaning silent cutter), which used a chain to transmit power from the rear roller to the cutting cylinder. The machine was much lighter and quieter than the gear driven machines that preceded them, and won first prize at the first lawn mower trial at the London Horticultural Gardens.[22] Thus began a great expansion in the lawn mower production in the 1860s. James Sumner of Lancashire patented the first steam-powered lawn mower in 1893.[23] Around 1900, Ransomes' Automaton, available in chain- or gear-driven models, dominated the British market. In 1902, Ransomes produced the first commercially available mower powered by an internal combustion gasoline engine. JP Engineering of Leicester, founded after World War I, invented the first riding mowers.[citation needed]